Lean

- 5 minute read

Foster a culture of continuous improvement and empower Lean transformations with real-time data visualization.

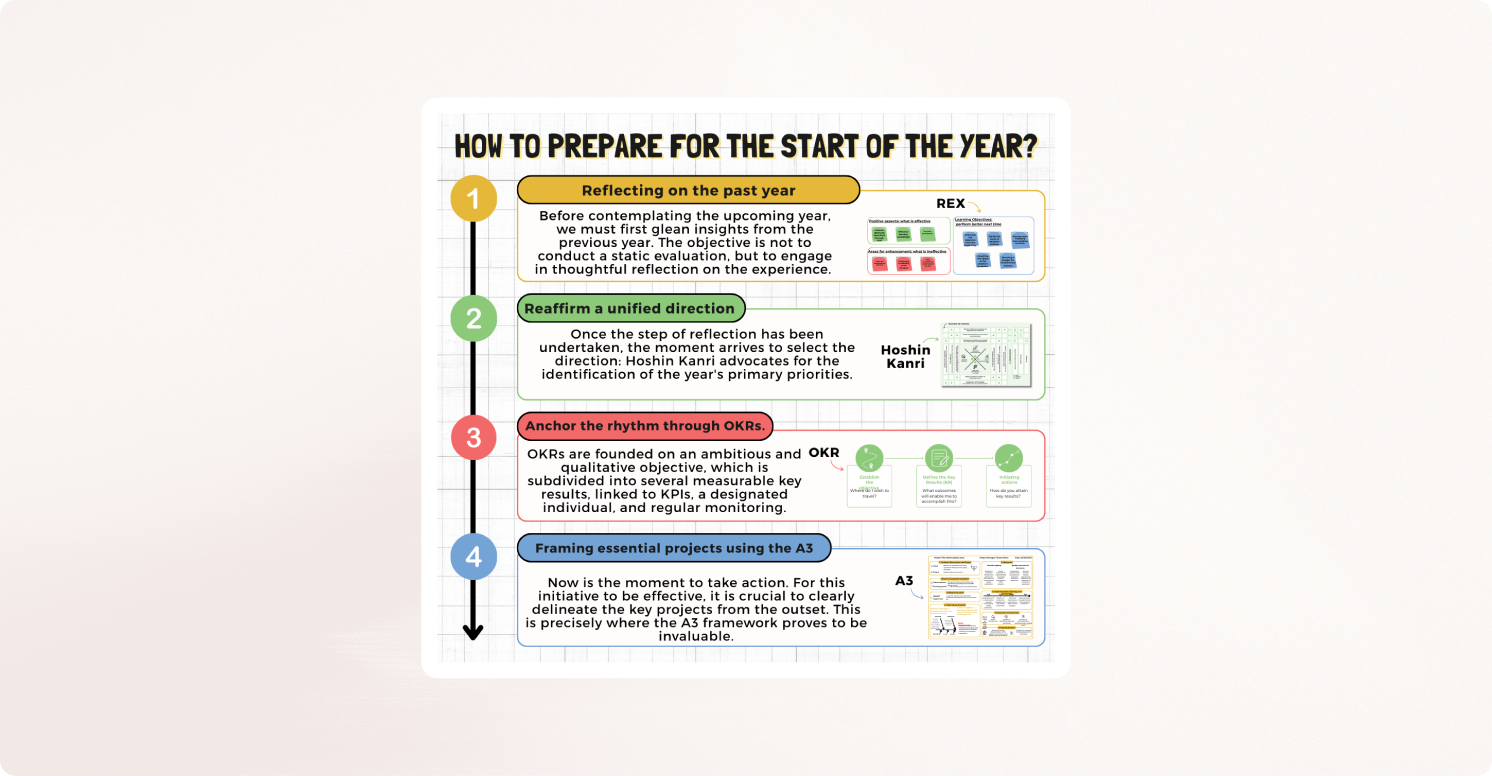

Before projecting yourself into the year ahead, you first need to learn from the year that has just ended. This is precisely where the Kaizen philosophy comes into play: observing, understanding, and drawing lessons from what has been experienced. The goal is not to produce a fixed annual review, but to build a real feedback loop.

What worked well? Where did we make progress? Which dysfunctions were tolerated? What did we learn collectively during difficult moments? My advice: take the time to run a closing ritual with your teams. The objective is to surface lessons learned and unspoken frustrations. This raw material is what allows you to build a genuine continuous improvement dynamic. Kaizen always starts with a posture of self questioning, even and especially when everything seems to be going well.

Once this step back has been taken, it is time to choose a direction. What Hoshin Kanri offers is a framework to ensure that strategy does not remain a positioning document or a back to work speech, but becomes a guiding thread for the entire organization. The core idea is simple: define the major priorities for the year, often referred to as strategic breakthroughs, and translate them into concrete objectives at every level.

This alignment process is not a top down exercise frozen once and for all. It is a dialogue between leadership and teams, between strategy and operations. Things are adjusted, clarified, refined. The goal is not to have a perfect plan, but a clear and understandable direction that can guide efforts without creating confusion.

From there, several steps are essential to build an effective and engaging Hoshin. First, you need to formulate a clear and ambitious vision. This long term vision is translated into three to four strategic objectives to be achieved over a three to five year horizon. To be actionable, these objectives must be defined in a SMART way, meaning specific, measurable, achievable, realistic, and time bound.

Once this compass is set, the next step is to translate the vision into annual objectives. These objectives act as milestones toward long term ambitions. They must be both challenging and achievable, and concrete enough to guide day to day actions.

Then comes the transformation of these objectives into concrete improvement initiatives. Objectives are broken down into specific actions, assigned at each level of the organization: leadership, departments, and frontline teams. Each entity must understand its role and its contribution to achieving the overall vision. This is often referred to as cascading objectives.

But setting objectives is not enough. You also need to ensure that progress is heading in the right direction. This is where simple yet relevant tracking indicators are defined to regularly assess progress. These indicators provide a shared management framework and make progress visible.

Finally, a last step that is often overlooked but absolutely critical is the assignment of responsibilities. Who does what? Who executes? Who supports? Who decides? Models such as RACI or EAD are often used to clarify roles. The principle is simple: for each action, one person is accountable for delivery, even if others contribute.

For some organizations, Hoshin Kanri can feel too heavy or too macro. This is where OKRs, Objectives and Key Results, usefully complement the approach. Popularized by Google in the 2000s, OKRs offer a more agile and rhythmic way to manage objectives, based on a simple principle: one ambitious, inspiring, qualitative objective supported by two to three key results that are measurable, concrete, and achievable within a short time frame, usually a quarter.

Each key result is associated with clear KPIs and an identified owner who is accountable for progress. What really makes OKRs powerful is the frequent follow up. This light but regular ritual helps keep direction, anticipate deviations, and most importantly create a collective dynamic focused on progress rather than only the final outcome. My recommendation is to review OKRs every two weeks.

At this stage, you have identified what needs to evolve through Kaizen, you have set a clear direction with Hoshin, and you have translated that ambition into short term objectives with OKRs. Now it is time to act. But be careful: for action to be effective, key projects must be properly framed from the start. This is exactly where the A3 becomes essential.

The A3 framing document is the tool I systematically recommend when launching a project or an improvement initiative. On a single page, it forces you to clarify the fundamentals: what problem are we trying to solve? why does it matter? what is the current situation? what are the root causes? who is involved? what is the action plan? what indicators will be used to track progress?

My advice: adopt the A3 as a reflex for your transformation projects. Not as an extra formality, but as a real thinking framework. Writing things down forces you to structure your reasoning, ensure everyone is talking about the same problem, and ask the right questions before jumping to solutions.

It also creates a clear record of decisions, which is extremely valuable for follow up. In short, the A3 helps you move faster because you took the time to start properly.

Across all these tools, what is truly at stake is the quality of dialogue within the organization. Preparing the year well is not about producing documents. It is about creating the conditions for teams to understand, take ownership of, and contribute to the strategy. It is about turning direction into action, and intention into collective learning.